When a worker leaves for a shift and returns without a limb, the impact extends far beyond the operating room. In workers’ compensation, you are not only managing wage loss and medical bills. You are also influencing whether that person can walk, work, parent, and participate in their own life again.

Prosthetics sit at the center of that recovery story. They are also one of the costliest and most misunderstood elements in a workers’ compensation claim.

This article distills key insights from our Injury Insight webinar, Prosthetic Considerations for the Injured Worker, featuring internationally recognized prosthetist Dale Berry, CP, FAAOP, LP.

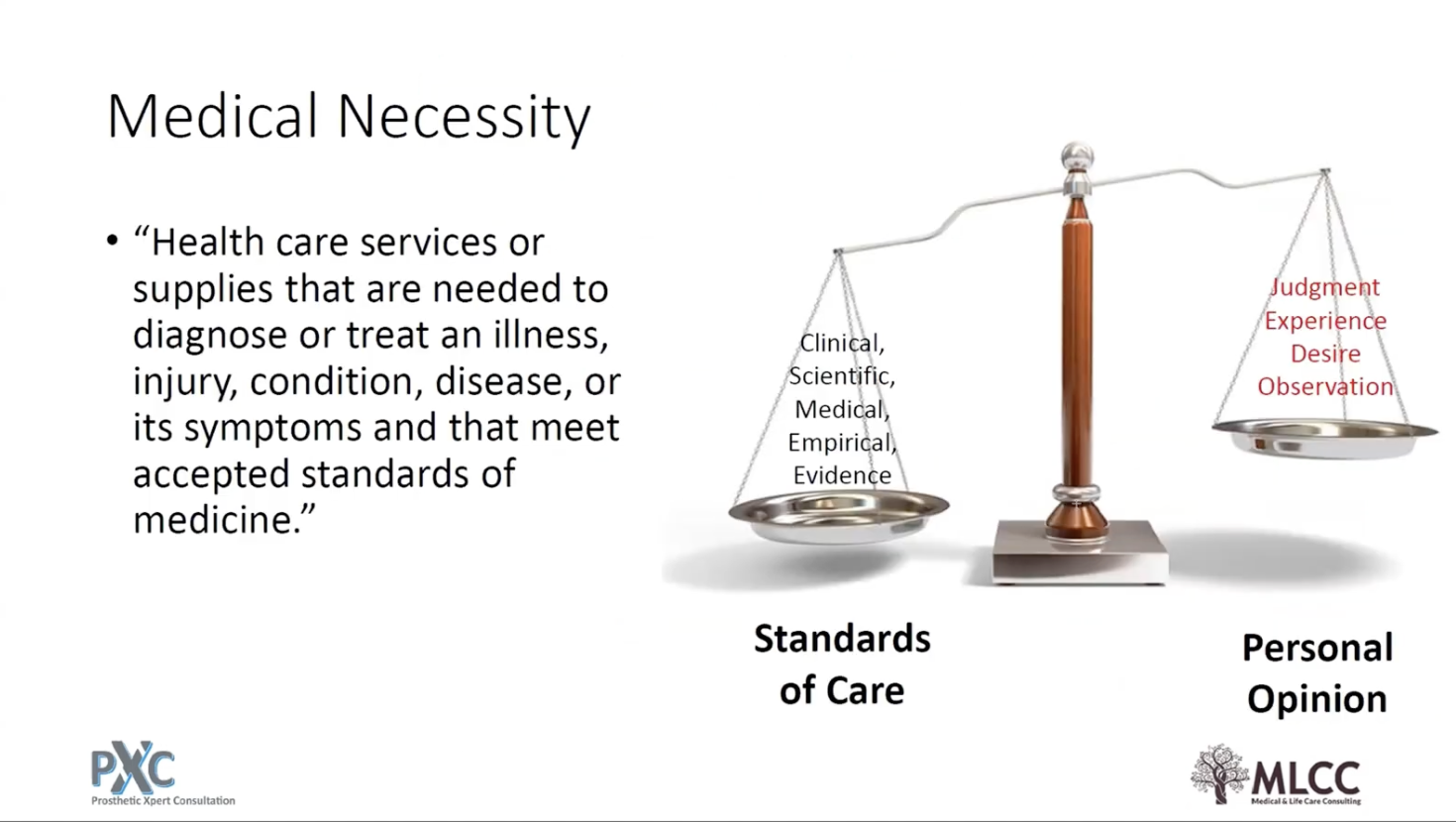

Medical Necessity in a Workers’ Compensation Context

Every state has its own workers’ compensation regulations, but one principle is consistent. When a worker loses a limb in a covered injury, the carrier is responsible for providing the apparatus that allows them to function as safely and independently as possible.

In practical terms, that usually means prosthetics.

However, in workers’ compensation, the question is not just:

“Does this worker qualify for a prosthesis?”

It is also:

“Which prosthesis is medically necessary and reasonable for this injured worker, given their injury, comorbidities, job demands, and stage of recovery?”

Medical necessity is typically defined as services or supplies that diagnose or treat an illness or injury, and that meet acceptable medical standards. Losing a limb clearly satisfies that threshold. But not every amputee is an appropriate prosthetic candidate.

A prosthesis is a tool. In workers’ compensation, paying for a device the worker cannot safely use does not meet the standard of reasonable and necessary care.

For each case, you are weighing:

- Standards of care and evidence Functional assessments, comorbidities, contralateral limb status, fall risk, age, and rehabilitation potential.

- Patient preference and expectations Many workers arrive with strong opinions after researching online. Their motivation is valuable. Their expectations often need guidance.

In a workers’ compensation setting, you must protect both the worker’s function and the integrity of the claim. That means asking whether the requested technology is clinically appropriate, not simply whether it exists.

What You Are Actually Paying For When You Approve “A Leg”

From a workers’ compensation standpoint, “prosthetic leg” sounds like a single line item. In reality, each prosthesis has three major components that drive cost and outcomes:

1. The socket

- Custom fabricated to fit that worker’s residual limb

- Accounts for scar tissue, soft tissue, bone, and skin tolerance

- No two sockets are identical

2. The components

- Knees, feet, pylons, connectors, microprocessors, batteries, covers

- Each with specific weight limits and activity ratings

- Chosen based on job demands, terrain, and functional level

3. The alignment and fitting process

- How all the parts are assembled, adjusted, and tuned to the worker

- Includes repeated visits, small modifications, and dynamic alignment

When you approve a prosthesis, you are not just approving individual parts. You are approving a clinical system that must work together for that worker’s body, job, and environment.

Why Time Matters: Limb Maturation and Staged Devices

Workers’ compensation professionals often think in terms of dates of injury and maximum medical improvement. Prosthetics sit on a different timeline, driven by how the residual limb changes after surgery.

Typical pattern for a lower limb amputation:

-

Immediately post-op

Residual limb is swollen, tender, sutured, and unstable. -

First 6 to 12 months

Edema gradually resolves, muscles atrophy, and the limb shrinks. Socket fit changes frequently. -

Around 24 months

The limb is usually “mature,” with a more stable size and shape.

Because of this, a prosthetic plan for a workers’ compensation case is staged:

1. Preparatory prosthesis

- Simple, light device with a larger socket

- Focused on standing, balance, and basic walking

- Designed to be adjusted or replaced as the worker’s limb shrinks

2. Replacement sockets during the early phase

- Components may stay the same

- Socket is remade as the limb reduces in volume

- Essential for maintaining function and preventing skin breakdown

3. Definitive prosthesis

- Provided once the limb is more mature

- Can incorporate more advanced technology if clinically appropriate

- Intended for long term community ambulation and work demands

For reserving and settlement discussions, you should expect:

- Significant prosthetic adjustments and socket changes in the first 6 to 24 months

- A staged approach rather than a single “permanent” leg delivered immediately after surgery

The Five Year Replacement Cycle: Long Term Workers’ Compensation Exposure

For an injured worker who continues to use a prosthesis, there is a predictable long term pattern of costs:

2. The components

- Prosthesis replacement approximately every 5 years

- Midcycle replacement socket around year 2 or 3

- Ongoing maintenance and supplies every year (Liners, Socks, Foot or knee servicing, Straps and suspension components)

In physically demanding occupations, devices may wear faster. If a worker is in their 30s or 40s, a lifetime workers’ compensation claim may reasonably involve multiple prosthetic cycles.

When you are setting reserves, negotiating settlements, or reviewing life care plans, a five year replacement cycle with midcycle socket change is a clinically realistic assumption for an active prosthesis user.

Functional Levels and Job Demands: Matching Technology to Real Life

Functional levels, often referred to as K levels, are central to prosthetic justification.

- K0 – No ability to ambulate or transfer safely. Not a prosthetic candidate.

- K1 – Household ambulator, limited walking on level surfaces.

- K2 – Limited community ambulator, occasional curbs, ramps, and grass.

- K3 – Unlimited community ambulator, variable cadence, full community mobility.

- K4 – Highly active individual or athlete, frequent high impact activities.

In workers’ compensation, understanding the intersection of K level and job demands is critical:

- An office worker in an urban setting may be K3 due to daily community walking, stairs, and variable surfaces.

- A construction worker on uneven terrain may require different feet or shock absorbing components, even if both are K3.

- A firefighter or police officer with an above knee amputation may justify K4 level technology and military grade components due to impact and environmental demands

The key insight:

A higher K level component does not upgrade a lower K level worker.

Paying for K3 or K4 technology does not turn a limited community ambulator into a full community ambulator. In fact, mismatching technology to functional level can make gait worse and increase fall risk.

When reviewing recommendations, ask:

- What is the documented K level for this worker?

- How was it determined?

- Do the proposed components match the K level and job description?

Microprocessor Knees, Feet, and the “Wild West” of Work Comp

In group health and Medicare, prosthetic billing is tightly controlled. Workers’ compensation, by contrast, often functions more like a “wild west,” especially in states without strict fee schedules.

Microprocessor knees and advanced feet are powerful tools for the right injured worker. They can:

- Improve safety on stairs and uneven ground

- Allow variable cadence and controlled descent

- Reduce falls and energy expenditure

But they also:

- Add significant weight

- Require training and maintenance

- Increase device and replacement costs

Some devices were designed for military environments, with features like:

- Prolonged salt water resistance

- Extra rugged casings for jumping from vehicles or aircraft

- Extended battery life for days in the field without electricity

Those features are clinically justified for certain civilian roles, such as:

- Firefighters

- Police officers

- Workers in remote outdoor environments for days at a time

They are not automatically justified for a desk-based worker in an office building with ready access to power and dry flooring.

In a workers’ compensation review, you should expect the prosthetist to connect the dots:

- Here is the worker’s K level

- Here is their job description and environment

- Here are the specific features of this device that are medically necessary for that situation

Upper Extremity Cases: Return to Work and Practical Function

Upper extremity amputations can be especially complex in workers’ compensation, particularly for workers who rely heavily on their hands:

- Mechanics

- Electricians

- Machine operators

- Line workers

The optimal plan is often two prosthetic arms for one limb:

1.Body powered prosthesis (initial)

- Lighter, durable, and easier to adjust during limb changes

- Helps the worker build tolerance and learn basic function

- Useful long term for heavy duty tasks, outdoor work, or wet environments

2. Myoelectric prosthesis (once limb stabilizes)

- Lighter, durable, and easier to adjust during limb changes

- Helps the worker build tolerance and learn basic function

- Useful long term for heavy duty tasks, outdoor work, or wet environments

From a workers’ compensation standpoint, this is not excess. It is a recognition that no single prosthetic device can handle the full range of human tasks, especially for workers with both physical and public facing roles.

For partial hand injuries, detailed anatomy matters. Knowing which fingers and which joint levels are involved will determine whether devices like PIP drivers, MCP drivers, or partial hand myoelectric systems are appropriate. These can be central to restoring grip strength, tool use, and protection from overuse of the remaining thumb.

Coding, Pricing, and Protecting the Integrity of the Claim

Prosthetic billing relies on L codes:

- Upper extremity: L6000–L7499

- Lower extremity: L5000–L5990

In workers’ compensation, pay attention to:

1. Your state’s rules

- Fixed fee schedules

- Percent of billed charges

- Reference to Medicare, federal schedules, or none at all

2. Use of 99 codes

- Codes ending in “99” are miscellaneous

- Appropriate for truly new, uncoded products

- Often misused to unbundle one device into multiple “pseudo components”

3. Evaluation charges

- Basic clinical evaluation is typically part of delivering a prosthesis

- Large stand alone “diagnostic” bills using miscellaneous codes should trigger questions

If you see multiple 99 codes on a single claim, or charges that are dramatically out of line with Medicare or federal workers’ compensation fee schedules, treat that as a signal to request detailed documentation and justification.

The goal is not to undercut necessary care. The goal is to ensure that the injured worker receives appropriate, evidence based technology without unnecessary inflation of claim costs.

Practical Questions to Ask on Every Prosthetic Work Comp File

When you review a prosthetic request or life care plan for an injured worker, consider:

- Is the worker a true prosthetic candidate based on function, comorbidities, and contralateral limb status?

- Where are they in the healing timeline? Preparatory device, early adjustments, or definitive limb?

- What is their documented K level and how does it align with their actual job demands?

- Do the proposed components match that K level and environment, or are they aspirational?

- Does the plan reflect a realistic five year replacement cycle and midcycle socket replacement?

- Is there a clear rationale for microprocessor or military grade components tied to job demands?

- For upper extremity and partial hand cases, is there a staged plan and recognition that more than one device may be needed?

- Are codes and charges consistent with Medicare or workers’ compensation reference schedules, without excessive use of 99 codes?

The “best” prosthesis in workers’ compensation is not the most expensive option available. It is the device or combination of devices that:

- Matches the worker’s functional level

- Aligns with the job and environment

- Reflects the healing timeline

- Follows standards of care

- And supports safe, sustainable function over the life of the claim

When those elements line up, workers’ compensation can be a powerful mechanism not only for covering costs, but for genuinely restoring a worker’s ability to move forward with dignity and purpose after limb loss.

How Medical & Life Care Consulting Services Supports Prosthetic Workers’ Compensation Cases

Navigating prosthetic care within a workers’ compensation claim requires far more than simply approving a device. It demands coordinated medical oversight, vocational awareness, cost forecasting, and long term planning. That is where Medical & Life Care Consulting Services plays a critical role.

Our nurse case managers and medico-legal consultants work alongside carriers, employers, attorneys, and injured workers to ensure that prosthetic care is:

- Clinically appropriate based on functional level, comorbidities, and job demands

- Medically necessary and defensible under workers’ compensation standards

- Properly staged across the preparatory and definitive prosthetic phases

- Accurately projected for long term exposure, reserves, and settlement planning

Through medical case management, life care planning, and medico-legal consulting, our team helps translate complex prosthetic recommendations into clear, evidence based strategies for injured workers and the professionals supporting them.

Whether a case involves an early traumatic amputation, a partial hand injury affecting return to work, or long term prosthetic cost forecasting for settlement purposes, MLCC provides the clinical insight and coordination needed to support both recovery and claim integrity.

To learn more about how MLCC supports prosthetic and catastrophic workers’ compensation cases, schedule a complimentary consultation with our team to discuss your complex injury needs.