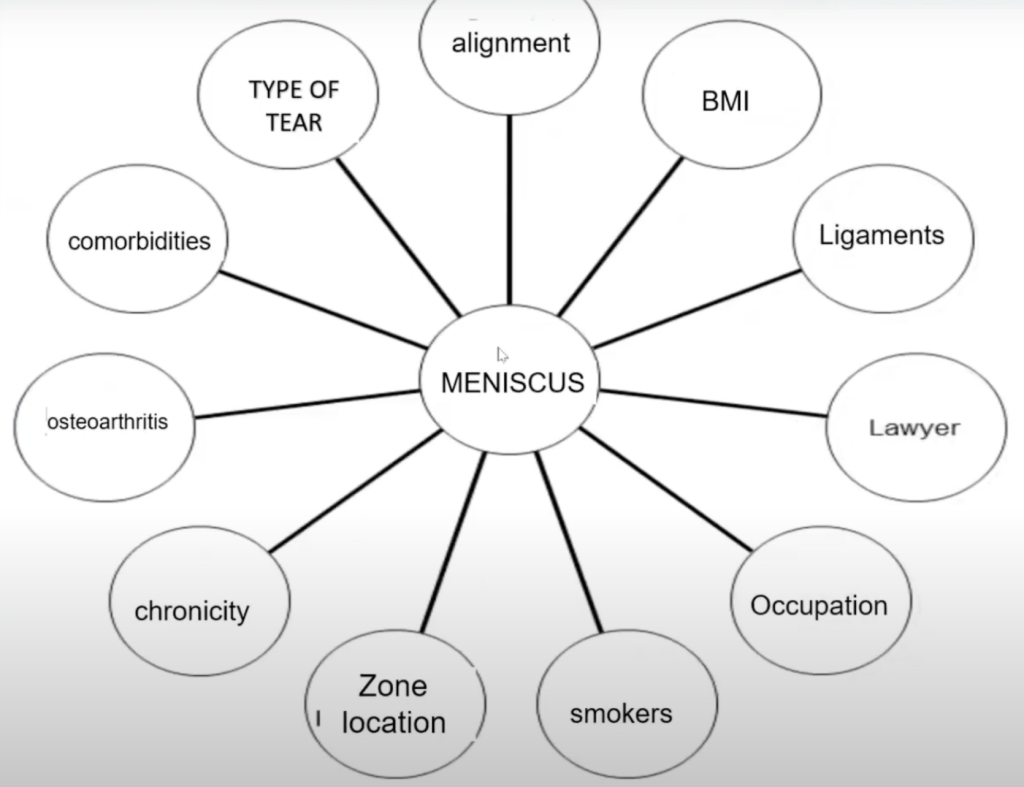

Meniscus tears are one of the most common and impactful knee injuries, affecting mobility, stability, and long-term joint health. For years, there has been debate about when surgery is necessary, when conservative management is appropriate, and what the true consequences of meniscus loss are.

In this Injury Insight session, orthopedic surgeon Dr. Brian McKeon provides a comprehensive review of meniscus anatomy, biomechanics, and the latest surgical approaches. His expert perspective helps clarify the complexities of diagnosis and treatment, offering valuable guidance for healthcare professionals, students, and anyone seeking a deeper understanding of this critical knee injury.

Why the Meniscus Matters

The meniscus is a crescent-shaped piece of fibrocartilage located between the femur and tibia. Each knee has two—the medial and lateral menisci—that serve as shock absorbers, stabilizers, and protectors of the articular cartilage.

Key functions include:

- Load distribution: During activities like climbing stairs or squatting, the meniscus absorbs forces up to 10–15 times body weight.

- Joint stability: With convex and concave bone surfaces meeting at the knee, the meniscus adds critical stability. Without it, ligaments and cartilage take on more stress.

- Shock absorption and lubrication: The meniscus acts like a gasket, spreading forces evenly while protecting cartilage and reducing wear.

An easy way to visualize its role is to think of a sponge under pressure: the meniscus compresses, redistributes load, and then rebounds. Without this mechanism, forces concentrate on small areas of cartilage, leading to accelerated breakdown and early arthritis.

Biomechanics and Vulnerabilities

The strength of the meniscus comes from its circumferential collagen fibers, also called hoop stresses. These fibers are like the steel bands on a wine barrel. When intact, they contain pressure and maintain stability. When cut across by a radial tear, the system fails—the meniscus may still appear present, but functionally, it is lost.

Another biomechanical challenge is meniscal extrusion, where the meniscus slips out of the joint line. On imaging, this looks like a black structure shifted away from the tibial plateau. When extruded, the meniscus cannot perform its role, even if no clear tear is visible. Extrusion is a strong predictor of pain, degeneration, and poor long-term outcomes.

Types of Meniscus Tears

Not all tears are equal. Understanding the pattern and location is crucial for guiding treatment.

- Radial tears – Slice through hoop fibers, often rendering the meniscus nonfunctional.

- Bucket handle tears – Large, displaced fragments that can lock the knee.

- Root tears – Occur where the meniscus anchors to bone; extremely destabilizing and often painful.

- Degenerative tears – Common in older adults, often linked with arthritis and gradual wear.

Blood supply is another key factor. Tears in the red-red zone (outer edge with good vascularity) may heal when repaired. Those in the white-white zone (inner edge with little to no blood supply) have limited healing potential.

The Shift from Removal to Repair

For years, the standard response to meniscus injury was meniscectomy—removing the damaged portion or, in some cases, the entire meniscus. This often relieved short-term symptoms but carried serious long-term consequences. Patients frequently developed early arthritis and required knee replacement much sooner than expected.

Long-term studies now confirm: removing the meniscus almost guarantees accelerated degeneration.

This evidence has driven a major shift:

- Meniscectomy still has a place for small, inner-edge tears with little biomechanical consequence.

- Meniscus repair has become the gold standard for most injuries, especially radial and root tears.

Repair techniques are more technically demanding and involve longer recovery, but they preserve function and delay joint deterioration—critical for both athletes and workers in physically demanding roles.

Advances in Surgical Approaches

Contemporary surgical practice offers multiple strategies to save and restore the meniscus.

- Meniscus centralization (lift technique): Used when the meniscus is extruded. Anchors reposition it into the joint, restoring alignment and function.

- Root repair: Rather than debriding the torn root, surgeons reattach it using sutures and bone tunnels. This prevents rapid progression to arthritis.

- Meniscus transplantation: For younger patients with irreparable damage, donor meniscus tissue can restore anatomy and delay joint replacement.

- Biologic and synthetic implants: Collagen scaffolds, plastic substitutes, and even metal shims have been tested. While durability remains a challenge, ongoing research continues to refine these innovations.

The overall trend is clear: the surgical pendulum has swung away from excision and toward reconstruction.

The Arthroscopy Debate

Few orthopedic procedures have been as controversial as knee arthroscopy. Randomized trials in patients with degenerative tears showed little difference between arthroscopy and sham surgery, leading to questions about the value of the procedure.

These findings have shaped insurance policies and public perception, with some headlines questioning whether arthroscopy should be done at all.

The reality is more nuanced. While routine scoping of degenerative tears may offer little benefit, ignoring acute radial or root tears can be devastating. These injuries often require timely surgical repair to prevent further joint damage.

The challenge is classification: identifying which patients benefit from conservative care and which need intervention. Broad generalizations—“arthroscopy doesn’t work”—do not reflect the complexity of meniscal pathology.

Recovery and Patient Expectations

Meniscus repair is not a quick fix. Recovery can take six to eight months, with restrictions on weightbearing, bracing, and activity. Patients often find the process frustrating compared to the faster turnaround of meniscectomy.

Yet the trade-off is worthwhile. Preserving the meniscus significantly improves long-term joint health, reduces the likelihood of arthritis, and helps patients avoid total knee replacement.

For case managers and claims professionals, this means recognizing:

- A longer recovery does not equal poorer care.

- Early investment in proper repair can reduce long-term disability and medical costs.

- Patient education and expectation management are critical for compliance and outcomes.

Looking Ahead

The meniscus is no longer viewed as expendable tissue. It is now recognized as central to knee health. With advances in repair, transplantation, and biologics, treatment strategies continue to evolve. The most important principle is preservation—removing the meniscus should be the last resort, not the first option.

For patients, clinicians, and the professionals who guide recovery planning, this shift represents progress. By prioritizing meniscus preservation, the medical community can help more individuals maintain mobility, delay arthritis, and improve long-term quality of life.

Conclusion

Meniscus tears are complex injuries. Each case demands careful analysis of tear type, biomechanics, vascularity, and patient needs. While surgery once meant routine removal, today the focus is on saving and restoring the meniscus whenever possible.

For those navigating treatment and recovery—whether in clinical practice, claims management, or legal review—understanding these nuances is essential. The difference between a removed and a repaired meniscus can shape a patient’s entire future.